Winter Steelhead of the North Santiam River

As winter gives way to the cold rains of spring in the North Santiam Canyon, newly hatched steelhead fry begin to wriggle their way to the surface of their gravel nest. In the cold waters of a tributary stream above the North Santiam River, their stream, they face a long and harrowing journey that will take them to the sea, include a couple of circuits of the Northern Pacific Ocean, and eventually bring them home again to the very stream of their birth. It’s a journey full of challenges and danger. Few will survive.

The winter steelhead who do return to the North Santiam River are the wary survivalists, attuned to their environment, who beat the odds and survived three, four, or five years and migratory journeys of hundreds maybe thousands of miles. These elite survivors withstood the challenge of marginal habitat and water pollution, natural predators and disease. They negotiate the Bennett Dams at Geren Island on their way down to the sea and again on their homeward journey. Yet they return answering the primal drive to return, reproduce, to survive and thrive.

[box size=”large” style=”rounded”]The winter steelhead of the North Santiam are oceangoing (or anadromous) rainbow trout. They are born in freshwater streams that flow into the North Santiam River, spend their adult lives in the northern Pacific, and return to their freshwater home streams to spawn.[hr] Anadromous comes from the Latin word ana which means up, as in upstream, and dromous meaning moving or migrating.[/box]

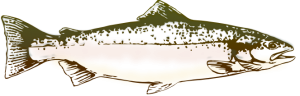

Spawning

Males tend to arrive on spawning grounds before females and establish a dominance hierarchy based mostly on body size.

As spawning time nears the female steelhead finds just the right graveled stream bottom. Rolling to her side, she’ll excavate a depression a foot or two across and several inches deep using strong tail flicks to swoosh the gravel up which the stream current then carries out of the way. And that’s the way she excavates the nest. She’ll then deposit maybe a quarter or less of the eggs she’s carrying in the nest, move off the nest and allow the male access. He releases his sperm in a milky matrix which washes over the eggs.

Once her male suitor has fertilized the egg, she moves just upstream of the nest and excavates another one. In the process of creating her second nest, the material she removes is carried downstream to cover the first.

An adult female steelhead will produce about 900-1000 eggs per pound of her body weight.

And so they continue forming four, five, or six nests until the female steelhead has deposited her entire egg supply. The collection of these nests is referred to as a redd.

Once the last nest has been covered, the spent female’s rearing duties are finished. She may spend a little time on the redd recovering but it won’t be long before she resume feedings. She needs to rebuild her strength because, unlike salmon which die soon after spawning, steelhead return to the ocean and with luck will be back to the same stream to repeat the procreative drama next year.

Male steelhead will seek additional mating opportunities with females who arrive later in the season, expending so much effort seeking mates and challenging their competitors that they normally die after a single spawning season.

Development

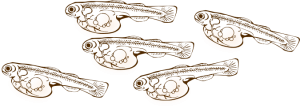

The buried, fertilized eggs develop and undergo a metamorphosis over the next 2 to 3 months. Slowly, the egg starts to “morph” into a tiny fish. In several weeks the egg has a small fish head and a small fish tail with a relatively huge belly which is the shrinking egg. Having provided the infant steelhead with nourishment up to this point, the egg will eventually be entirely absorbed.

The buried, fertilized eggs develop and undergo a metamorphosis over the next 2 to 3 months. Slowly, the egg starts to “morph” into a tiny fish. In several weeks the egg has a small fish head and a small fish tail with a relatively huge belly which is the shrinking egg. Having provided the infant steelhead with nourishment up to this point, the egg will eventually be entirely absorbed.

The completion time for the final absorption of the egg depends on water temperature, taking longer in colder water. Then, the luckiest, strongest little steelhead, called fry, will wriggle through the gravel maze into the open expanse of the stream.

Most of a steelhead fry’s nest mates don’t make it, never emerging from where they were  “hatched”. The tiny survivors face two daunting tasks: searching for food, and avoiding becoming food. many more of his baby steelhead comrades who’ve made it this far will not survive their first few weeks in open water, having been eaten, starved, or swept to their deaths, unable to find shelter in raging winter river flows. For those that do make it through their first year in the river, many, again, will not see their second.

“hatched”. The tiny survivors face two daunting tasks: searching for food, and avoiding becoming food. many more of his baby steelhead comrades who’ve made it this far will not survive their first few weeks in open water, having been eaten, starved, or swept to their deaths, unable to find shelter in raging winter river flows. For those that do make it through their first year in the river, many, again, will not see their second.

Newly emerged steelhead fry swim freely, exploring their spacious, dangerous environment.

Initially, the tiny fry school in quiet protected portions of the stream, usually along its periphery. Here they are sheltered from strong currents and predators as they forage for food items. Their diet consists mostly of small aquatic insects. In the first weeks the mortality rate can be very high for these free-swimming roamers.

As the steelhead grow over the next few months, the tendency to school disappears. For the next year or two, immature steelhead lead a solitary existence focused on food and survival.

Migration

It is usually in the spring at age two when most of North Santiam steelhead juveniles begin a journey downstream that will eventually lead them to the Pacific Ocean.

The outbound migrants, called smolts, just go with the flow. Down to the sea. That is, of course, if they survive the trials from dams, predators, disease, injury, and potentially lethal high water temperatures. Most who start won’t make it to saltwater. Those who do, make their way hundreds, if not a thousand miles or more, out into the Pacific Ocean.

After two years (for most) of accelerated growth and the building of fat reserves, they respond to their inner clocks, and turn general direction of their freshwater origins.

Apparently, iron-bearing structures in some of the body’s cells orient the returning steelhead to magnetic north. Once near the coastline, the steelhead relies on its keen olfactory sense to pick up on the trace element “fingerprint” of its home stream. Like a hound on a scent, our North Santiam sojourners first find the Columbia, and then the Willamette as their upstream ascent begins.

The fish that started its epic travels at four to eight inches tipping the scales at a few ounces, will return home usually at 23” to 30”, weighing five to ten pounds, as determined by the favorability of its ocean environment, the abundance of food, and its genetic growth potential.

The story continues.